Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s sandbox, from those who inspired him to those who were inspired in turn.

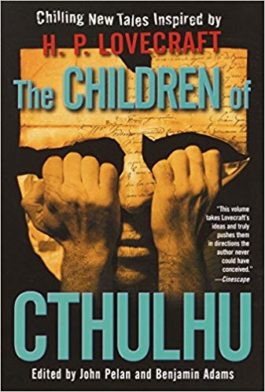

This week, we’re reading China Miéville’s “Details,” first published in 2002 in John Pelan and Benjamin Adams’ The Children of Cthulhu. Spoilers ahead.

“I don’t remember a time before I visited the yellow house for my mother.”

Summary

Narrator looks back to the time when he, a young boy, served as his mother’s emissary to housebound Mrs. Miller. Roombound, actually, for she never leaves the locked chamber just inside the door of a decrepit yellow house. Mrs. Miller’s other visitors include a young Asian woman, and two drunks, one boisterous, the other melancholic and angry. Narrator sometimes meets him at Mrs. Miller’s door, swearing in his cockney accent. Mrs. Miller remains undaunted, and eventually the drunk shambles miserably off.

Every Wednesday morning narrator visits Mrs. Miller, bringing a pudding his mother’s prepared from gelatin, milk, sugar and crushed vitamins. Sometimes he brings a pail of white paint. These he pushes in to Mrs. Miller through the merest gap of the door, open the merest second. From his brief glimpse inside, he sees the room is white, Mrs. Miller’s sleeves white plastic, her face an unmemorable middle-aged woman’s. While she eats, she answers the questions his mother sends with him: “Yes, she can take the heart of it out. Only she has to paint it with the special oil I told her about.” And “Tell your mother seven. But only four of them concern her and three of them used to be dead.”

One day Mrs. Miller asks narrator what he doesn’t want to do when he grows up. Thinking of his mother’s distress over letters from attorneys, narrator says he doesn’t want to be a lawyer. This delights Mrs. Miller, who warns him never to be tricked by small print. She’ll tell him a secret! The devil is in the details!

After this, narrator’s promoted beyond delivery boy to also reading aloud to Mrs. Miller. She confides in him: The Asian woman courts trouble, messing with “the wrong family.” Everyone “on that other side of things is a tricksy bastard who’ll kill you soon as look at you.” That includes “the gnarly, throat-tipped one” and “old hasty, who…had best remain nameless.” Another day, while the two drunks bicker outside, Mrs. Miller tells him about a special way of looking. There are things hidden right in front of us, things we see but don’t notice until we learn how. Someone has to teach us. So we have to make certain friends, which also means making enemies.

It’s about patterns. In clouds, or walls, or the branches of a tree. Suddenly you’ll see the picture in the pattern, the details. Read them, learn. But don’t disturb anything! And when you open that window, be damn careful what’s in the details doesn’t look back and see you.

The surly drunk grows belligerent, screaming that Mrs. Miller’s gone too far. Things are coming to a head—there’ll be hell to pay, and it’s all her own fault! The following week Mrs. Miller whispers a confession about the first time she “opened her eyes fully.” She had studied and learnt. She chose an old brick wall and stared until the physical components became pure vision, shape and line and shade. Messages, insinuations, secrets appeared. It was bliss. Then she resolved a clutch of lines into “something… terrible… something old and predatory and utterly terrible staring right back at me.”

Buy the Book

Middlegame

Then the terrible thing moved. It followed as she fled into a park, reappearing in the patterns of leaves, of fabric, of wheel spokes. Having caught her glance, it could move in whatever she saw. She covered her eyes and blundered home, seeing it whenever she peeked: crawling, leaping, baying.

Mrs. Miller tells narrator she considered putting her eyes out. But what if she could close that window, unlearn how to see the details? Research is the thing. That’s why he’s reading to her. Meanwhile she lives in a room purged of details, painted flat white, without furniture, windows covered, body encased in plastic. She avoids looking at her hands. She eats bland white pudding. She opens and closes the door fast so she won’t glimpse narrator in all his rich detail. It would only take a second. The thing is always ready to pounce.

Narrator’s unsure how the newspapers can help but he keeps reading. Mrs. Miller confides how the whiteness of her sanctuary preys on her. How the thing “colonizes” her memories and dreams, appearing in the details of even happy memories.

One chilly spring morning, the drunken man’s asleep in Mrs. Miller’s hall. Narrator’s about to retrieve the bowl when he realizes the drunk’s holding his breath, tensing. He manages one warning keen before the drunk throws him into the room, knocking back Mrs. Miller.

It’s narrator’s checked coat and patterned sweater that the drunk wants in the room. He pulls narrator himself back into the hall, slams and holds the door closed while Mrs. Miller screams and curses. Her terrified shrieks combine with “an audible illusion like another presence. Like a snarling voice. A lingering, hungry exhalation.”

Narrator runs home. His mother never asks him to return to the yellow house. He doesn’t try to find out what happened until a year later, when he visits Mrs. Miller’s room. His coat and sweater mildew in a corner. White paint crumbles from the walls, leaving patterns like rocky landscapes. On the far wall is a shape he approaches with “dumb curiosity far stronger than any fear.”

A “spreading anatomy” of cracks, seen from the right angle, looks like a screaming woman, one arm flung back, as if something drags her away. Where her “captor” would be is a huge patch of stained cement. “And in that dark infinity of markings, [narrator] could make out any shape [he] wanted.”

What’s Cyclopean: Things are hiding in the details, “brazen and invisible.”

The Degenerate Dutch: Mrs. Miller’s enemies, on top of everything else, call her some nastily gendered insults

Mythos Making: There are things man isn’t meant to perceive—and once you see them, you can’t unsee them.

Libronomicon: Mrs. Miller looks for the solution to her problems in “school textbooks, old and dull village histories, the occasional romantic novel.” Why not, if you can find answers anywhere?

Madness Takes Its Toll: It’s not paranoia if everything really is out to get you. On the other hand, living in a featureless white room isn’t great for anyone’s mental stability.

Anne’s Commentary

Because I am constantly making out faces and creatures and such-like in random cracks and splotches and airy masses of water vapor, I was glad to read that no less a genius than Leonardo da Vinci endorsed the practice:

“Not infrequently on walls in the confusion of different stones, in cracks, in the designs made by scum on stagnant water, in dying embers, covered over with a thin layer of ashes, in the outline of clouds, – it has happened to me to find a likeness of the most beautiful localities, with mountains, crags, rivers, plains and trees; also splendid battles, strange faces, full of inexplicable beauty; curious devils, monsters, and many astounding images. [For my art] I chose from them what I needed and supplied the rest.”

I guess Leonardo never had one of those curious devils or monsters look back at him, as was the misfortune of Miéville’s Mrs. Miller. We may also assume (mayn’t we?) that Leonardo wasn’t a friend of any tricksy bastard from the other side of things like that gnarly throat-tipped chap (Nyarlathotep?) or old hasty the best-left-nameless (Hastur, I bet.) But Mrs. Miller is. Someone guided her studies, taught her to open her eyes and see what’s hidden in plain sight, yet so rarely noticed. She’s a seer among seers, a witch among witches, in Miéville’s urban village. The belligerent drunk seems to be a peer down on his luck, servant of the same “other side” master. Narrator’s mother and the Asian woman seem to be informal acolytes. Others may come just to consult the sibyl.

Who has paid too much for her depth of vision. Once again we’re in the Person Who Sees/Learns Too Much territory. The teeming region of We Learn to Curse Curiosity and Bless Ignorance Too Late. The epigraph for “Details” is from Lovecraft’s “Shadow Out of Time,” but in the Mythos genealogy, this story is much more closely related to Frank Belknap Long’s “Hounds of Tindalos.” Here as there, ancient predators live in dimensions that can come perilously close to our own. Here as there, they fix on prey when they realize they are observed, when they return the gaze of the gazer—to catch their attention is deadly. Miéville’s interdimensional hunters have Long’s beat in this, however: While Long’s Hounds can advance only through angles, not curves, Miéville’s creature can travel through any random pattern Mrs. Miller sees, because she has opened to it the door into her perception.

Into, at last, not only what she sees, but what she remembers seeing or can imagine seeing. While it seems unable to attack though her memories or dreams, it can haunt them. It can drive her toward the miserable desperation narrator begins to witness. Did it matter what he read to her? Probably not. Probably for a while the pretense of “research” was enough, and the sound of a young, sympathetic voice.

So, to find the Hounds of Tindalos, you have to travel back to the deepest deeps of time. Miéville’s beasts prowl much nearer the surface. Intrepid reporter Carl Kolchak and I have downed copious quantities of our drugs of choice (Bourbon and Ben & Jerry’s, respectively) and gazed at a certain patch of mildew on the ceiling of the basement janitor’s closet in the Miskatonic U Library. Below we report our impressions:

Me: Definitely canine.

Carl: Except for the duck.

Me: What duck?

Carl: Over where the drainpipe comes out the ceiling.

Me: Oh. Yeah. The Drake of Tindalos.

Carl: Drake’s good. Rest are mutts. There’s, ah, Dachshunds of Tindalos.

Me: Chihuahuas.

Carl: Hell, no. Shih tzus.

Me: Yorkies.

Carl: Are you going to be serious? There are no Yorkies there. None. But over the spiderweb?

[Awed silence.]

Me: It’s—a Weimaraner.

Carl: That’s it.

Me: The Weimaraner of Tindalos.

[Awed silence.]

Carl: Y’know, that doesn’t look like a duck anymore…

Ruthanna’s Commentary

There are secrets hiding just beneath the surface of reality. Or maybe they’re not hiding—maybe it’s just that you haven’t noticed them yet. You might read the wrong book, or look the wrong way at the patterns in clouds. Hell, you might go on a deep and treacherous quest for the secrets of the universe—is that really so wrong? Do you really deserve what happens when the abyss looks back? Fair or otherwise, though, you can’t unsee. And quite possibly, you’ve disturbed something that doesn’t like being disturbed.

In a cosmic horror universe, this happens a lot. Mrs. Miller, though, stands out from the crowd in a couple of ways. First, in an endless list of men who find out and men who go too far, she’s a woman. Second, her survival time is measured not in days but in years. (Or so I infer from the apparent extent of Narrator’s childhood memories.)

First, the gender thing. There’s a bit of a progression here. Drunk guy calls her a whore—yes, that’s very original, thanks. Mrs. Miller wonders if she really had an important reason to look for answers in the details, or if she was just being nosy—gee, that’s an awfully gender-coded way of describing cosmic-scale curiosity, does Miéville know what he’s doing? And then finally, the story shifts from Hounds of Tindalos references to a woman stuck in the patterns of a wall, and I notice that Mrs. Miller’s house is yellow. Fine, Miéville knows exactly what he’s doing. Brazen and invisible indeed.

Part of what he’s doing, by replacing the archetypal curious-yet-repulsed Lovecraftian narrator, is digging into that trope and turning up some of the humanity. Mrs. Miller, unlike your average Miskatonic U gentleman professor, cries about her fate. Which is pretty reasonable. Her memories, colonized by the devil of the details, are pedestrian and sentimental: a pretty dress, a birthday cake. Yet she’s clearly as powerful as any one-step-too-far sorcerer, and even in her fallen state capable of passing oracular insight to those willing to brave her door (and her jello meals). The fact that she likes pretty dresses doesn’t make her one whit less a scholar, or one whit less doomed.

Except that as mentioned above, she is—almost—less doomed than your average over-curious protagonist. The most comparable is perhaps Halpin Chambers in “The Hounds of Tindalos.” Chalmers attracts the indefatigable attention of the hounds, locks himself in an angle-free room except for the paper he’s writing on, and immediately gets his head chopped off. Blackwood’s man who finds out lasts longer, but isn’t really fighting against his decline. Irwin’s poor reader sacrifices himself deliberately but inevitably. Miller, on the other hand, makes herself a successful angle-free, detail-free room, and makes plans to supply herself with both nutrition and research material. (There are a couple of bodily needs in there that we’re just not going to think about, but presumably she closes her eyes for those.) Smart, sensible, and determined, and it’s not really her fault that the necessary door-openings provide a point of vulnerability.

As the details are Miller’s greatest threat, they’re also the story’s strength. Details of breakfast, of clothes, of cracks in walls. The details of what a child notices and remembers. I love the oracular pronouncements we get to hear, sans questions: We have no idea what Narrator’s mom can take the heart out of, or which three of the seven used to be dead. There are whole other stories, maybe whole other devils, hidden within these brief glimpses, brazen and invisible.

Next week, we turn to a Nigerian take on weird fiction with Amos Tutuola’s “The Complete Gentleman.” You can find it (of course) in reread favorite The Weird.

Ruthanna Emrys is the author of the Innsmouth Legacy series, including Winter Tide and Deep Roots. She has several stories, neo-Lovecraftian and otherwise, available on Tor.com, most recently “The Word of Flesh and Soul.” Ruthanna can frequently be found online on Twitter and Patreon, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her young adult Mythos novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.

I think what intrigued me most here was the intersection of the mythos and folk magic. Mrs. Miller is clearly the neighborhood witch, dispensing useful advice, but not, due to her situation, cures and simples. Unless she’s offering recipes that we don’t hear about.She’s also clearly tangentially aware of the mythos and the beings it deals with it, but not in any formal (either scholarly or oral tradition) way. No training, she’s just heard about them and interpreted their names as best she can with her knowledge. Ruthanna touches on this a little. It’s what brought Aphra and Charlie together, but that’s still on a somewhat scholarly level. Blavatsky, Crowley and so on, while what Miéville shows us is more… visceral? Her magic isn’t necessarily based on a search for deeper truths and meaning, it’s just things you know about how to fix something or deal with a personal problem.

The drunk who brings about her end is clearly working for whatever it is that’s after her. Acolyte, cultist, something like that. Apparently there’s something it wants from her that she isn’t willing to give. It’s only after a fair amount of time with threats and negotiations that he finally resorts to violence. I wonder what it wanted originally.

Ruthanna and Anne (and Carl) saw the Hounds in this. For whatever reason, perhaps the chaotic nature of the random patterns, I felt that it was Azathoth after Mrs. Miller. (Also, Anne, may I suggest Bichon Frise? Far, far more annoying than Yorkies or Shih Tzu.)

This tale is also included in The Weird. I’d like to suggest the Michael Chabon story that immediately precedes it, “The God of Dark Laughter”, for the reread. It’s an unusual blend of Lovecraft, King and Ligotti.

I get echoes of Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s The Yellow Wallpaper. Woman confined to one room of a house (described as yellow) for the sake of her mental health, sees things in the walls, and eventually seems dragged into the pattern in the wall.

@DemetriosX, that’s interesting. I never thought of the drunk as an acolyte of the thing—I assumed he was acting on behalf of some former client unsatisfied with his oracle, or perhaps with her refusal to grant one: “He’s begging you, you old tart, please you owe him, he’s so bloody angry . . . only it ain’t you get the sharp end, is it?” Awful and destructive, but human. You don’t always need a devil to cause damage. A resentful man will do it just as well.

Having seen P.J. Hammond’s Sapphire & Steel (1979–82) since first reading this story, I have to say it now reminds me strongly of some aspects of “Assignment 4,” which may point to Miéville’s familiarity with the series or just its essentially Lovecraftian nature. (Or both.)

@Sovay: You make a good point. The rant you quote is rather ambiguous. Threats sandwiched by arguments from weakness, but that could easily come from someone who’s used to being a big fish in the pond. I think I was mostly swayed by the drunk knowing exactly how to hurt her. But then, what was mysterious to the narrator as a child doesn’t have to be unknown to the adults. OTOH, there was an air of letting the boy in on a big secret when she told him her story. Of course, whatever was after her could just as easily used whoever the drunk is working for to get at the old woman.

Hi

I will have to reread this now. I must admit when reading your post, Gilman’s The Yellow Wallpaper sprung to mind for me as well. I do like the Frank Belknap Long Hounds of Tindalos feel that we have here with the hidden multidimensional threat waiting in the very walls. Would earth itself have been destroyed if the narrator had been wearing paisley? Also I want to second DemetriosX’s suggestion that you consider tackling one of my favourite stories of all time, Chabon’s The God of Dark Laughter.

Regards

Guy

I read Details quite a few years ago and have never forgotten it’s disturbing premise..Have a listen to the old Poppy Family song Where Evil Grows for an interesting companion piece to the China M. story.

“The Asian woman courts trouble, messing with “the wrong family.”

I found that bit interesting – it suggests there are multiple “families” of eldritch abominations. You shouldn’t deal with Hasty and Gnarly’s family, they’re sneaky bastards. Perhaps there are other families which demand terrible prices but are fair in their bargains. Others which are indifferent to mortal wizards and anything they might have to offer. And still others which simply will do their best to destroy you on sight.

Perhaps Leonardo was safe simply because he lacked the concept of unspeakable alien entities. He might see devils, but they’d be conventional early modern devils, not indescribable atrocities capable of sucking your brain out through your eyeballs.

“Fine, Miéville knows exactly what he’s doing.”

Of course he does. Any time I suspect otherwise, I go back and read again! I’m a huge Miéville fan.

@7: I thought it was probably just the mundane. Probably literally “courting”. But Miéville doesn’t like to be that obvious. If a sentence isn’t working on more than one level, it isn’t doing its job. So, we’re probably both right.

The premise of this story reminds me of the odd children’s fantasy by John Keir Cross, The Other Side of Green Hills, (UK title: The Owl and the Pussycat) where a family of children discover an alternate dimension to the house and lands they live in, reachable by looking at it the right way. The mysterious old man known as Owl explains it by means of an optical illusion (the stacked cubes that can be seen as inward or outward turned) “Look once, look twice / Look round about. / And in a trice, / What’s In is Out.”

Like Cross’s short stories for adults (The Other Passenger) there’s an unsettling and sinister aspect to this, with the Moon People of the Other Side wanting to get hold of the youngest of the children, as they previously did with Pussycat, the Owl’s eternally young girl companion.

A review on Pretty Sinister Books, Here which also shows off Robin Jacques’ gorgeous and eerie illustrations.

(Hope that link shows up.)